Hey <<Name>>! If you missed last week's edition – history's most inspiring letters of motherly advice, the surprising science of motivation, Raymond Chandler on writing, and more – you can catch up here. And if you're enjoying this, please consider supporting with a modest donation.

Hey <<Name>>! If you missed last week's edition – history's most inspiring letters of motherly advice, the surprising science of motivation, Raymond Chandler on writing, and more – you can catch up here. And if you're enjoying this, please consider supporting with a modest donation.

"Imagine immensities, don’t compromise, and don’t waste time."

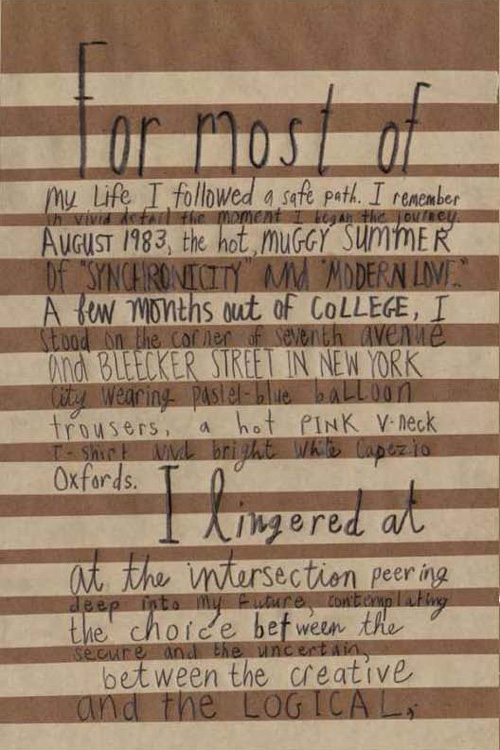

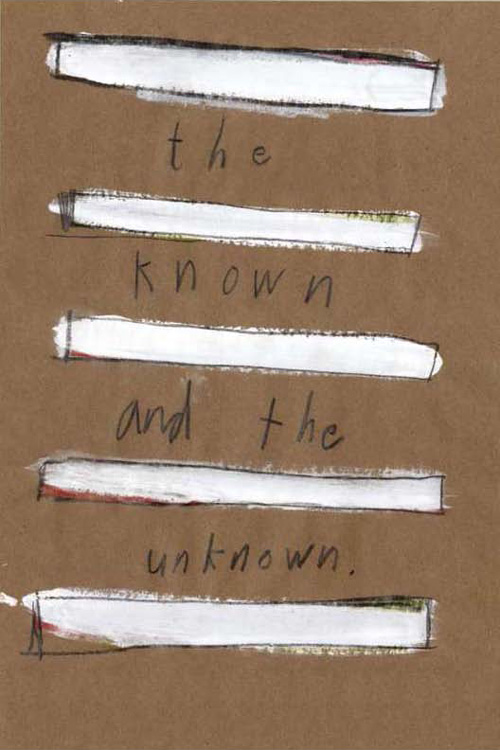

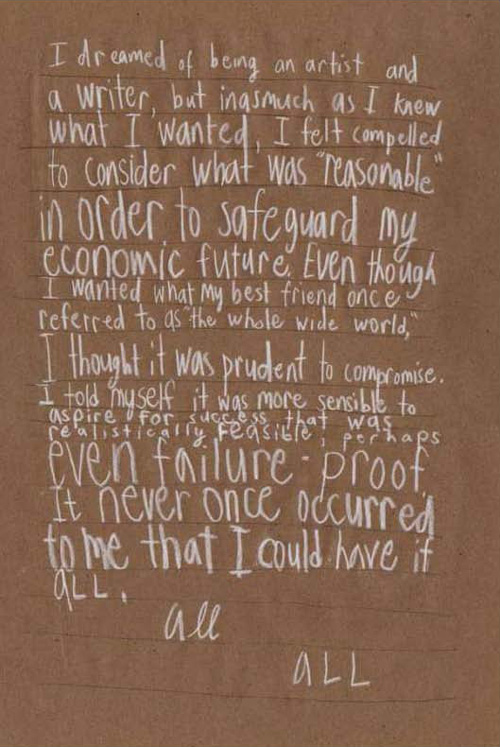

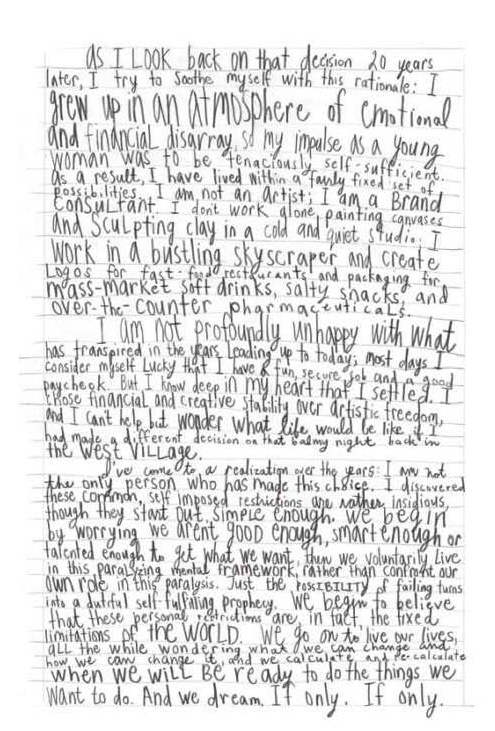

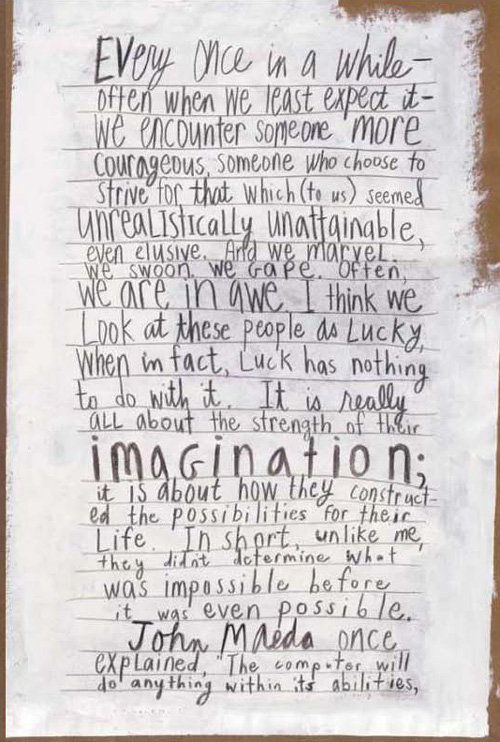

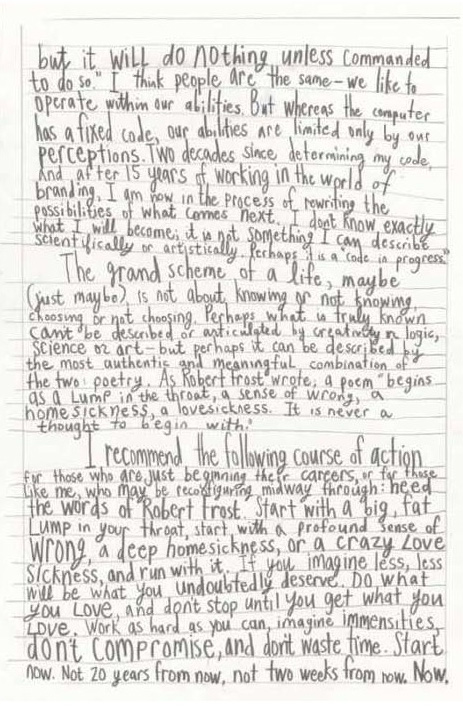

The seasonal trope of the commencement address is upon us as wisdom on life is being dispensed from graduation podiums around the world. After Greil Marcus's meditation on the essence of art and Neil Gaiman's counsel on the creative life, here comes a heartening speech by artist, strategist, and interviewer extraordinaire Debbie Millman, delivered to the graduating class at San Jose State University. The talk is based on an essay titled "Fail Safe" from her fantastic 2009 anthology Look Both Ways: Illustrated Essays on the Intersection of Life and Design (public library) and which has previously appeared on Literary Jukebox. The essay, which explores such existential skills as living with uncertainty, embracing the unfamiliar, allowing for not knowing, and cultivating what John Keats has famously termed "negative capability," is reproduced below with the artist's permission.

The seasonal trope of the commencement address is upon us as wisdom on life is being dispensed from graduation podiums around the world. After Greil Marcus's meditation on the essence of art and Neil Gaiman's counsel on the creative life, here comes a heartening speech by artist, strategist, and interviewer extraordinaire Debbie Millman, delivered to the graduating class at San Jose State University. The talk is based on an essay titled "Fail Safe" from her fantastic 2009 anthology Look Both Ways: Illustrated Essays on the Intersection of Life and Design (public library) and which has previously appeared on Literary Jukebox. The essay, which explores such existential skills as living with uncertainty, embracing the unfamiliar, allowing for not knowing, and cultivating what John Keats has famously termed "negative capability," is reproduced below with the artist's permission.

If you imagine less, less will be what you undoubtedly deserve. Do what you love, and don’t stop until you get what you love. Work as hard as you can, imagine immensities, don’t compromise, and don’t waste time. Start now. Not 20 years from now, not two weeks from now. Now.

If you imagine less, less will be what you undoubtedly deserve. Do what you love, and don’t stop until you get what you love. Work as hard as you can, imagine immensities, don’t compromise, and don’t waste time. Start now. Not 20 years from now, not two weeks from now. Now.

Look Both Ways: Illustrated Essays on the Intersection of Life and Design is an absolute treasure in its entirety, the kind of read you revisit again and again, only to discover new meaning and new access to yourself each time. It was preceded by How to Think Like a Great Graphic Designer and followed by the recent Brand Thinking and Other Noble Pursuits, both excellent in very different but invariably stimulating ways.

:: LOOK CLOSER / LISTEN / SHARE ::

What Goethe can teach us about cultivating a healthy relationship with our finances.

The question of how people spend and earn money has been a cultural obsession since the dawn of economic history, but the psychology behind it is sometimes surprising and often riddled with various anxieties. In How to Worry Less about Money (public library) – another great installment in The School of Life's heartening series reclaiming the traditional self-help genre as intelligent, non-self-helpy, yet immensely helpful guides to modern living, which previously gave us Philippa Perry's How to Stay Sane, Alain de Botton's How to Think More About Sex, and Roman Krznaric's How to Find Fulfilling Work – Melbourne Business School philosopher-in-residence John Armstrong guides us to arriving at our own "big views about money and its role in life," transcending the narrow and often oppressive conceptions of our monoculture.

The question of how people spend and earn money has been a cultural obsession since the dawn of economic history, but the psychology behind it is sometimes surprising and often riddled with various anxieties. In How to Worry Less about Money (public library) – another great installment in The School of Life's heartening series reclaiming the traditional self-help genre as intelligent, non-self-helpy, yet immensely helpful guides to modern living, which previously gave us Philippa Perry's How to Stay Sane, Alain de Botton's How to Think More About Sex, and Roman Krznaric's How to Find Fulfilling Work – Melbourne Business School philosopher-in-residence John Armstrong guides us to arriving at our own "big views about money and its role in life," transcending the narrow and often oppressive conceptions of our monoculture.

He begins with a crucial distinction, the heart of which echoes James Gordon Gilkey's 1934 advice on how not to worry. Armstrong writes:

This book is about worries. It's not about money troubles. There's a crucial difference.

Troubles are urgent. They ask for direct action. … By contrast, worries often say more about the worrier than about the world. … So, addressing money worries should be quite different from dealing with money troubles. To address our worries we have to give attention to the pattern of thinking (ideology) and to the scheme of values (culture) as these are played out in our won individual, private existences.

This book is about worries. It's not about money troubles. There's a crucial difference.

Troubles are urgent. They ask for direct action. … By contrast, worries often say more about the worrier than about the world. … So, addressing money worries should be quite different from dealing with money troubles. To address our worries we have to give attention to the pattern of thinking (ideology) and to the scheme of values (culture) as these are played out in our won individual, private existences.

While modern money-advice tends to fall into two main categories – how to get more money and how to get by on less – Armstrong points out that this bespeaks our culture's fixation on troubles rather than worries. He writes:

This is a problem because the theme of money is so deep and pervasive in our lives. One's relationship with money is lifelong, it colors one's sense of identity, it shapes one's attitude to other people, it connects and splits generations; money is the arena in which greed and generosity are played out, in which wisdom is exercised and folly committed. Freedom, desire, power, status, work, possession: these huge ideas that rule life are enacted, almost always, in and around money.

This is a problem because the theme of money is so deep and pervasive in our lives. One's relationship with money is lifelong, it colors one's sense of identity, it shapes one's attitude to other people, it connects and splits generations; money is the arena in which greed and generosity are played out, in which wisdom is exercised and folly committed. Freedom, desire, power, status, work, possession: these huge ideas that rule life are enacted, almost always, in and around money.

He draws an analogy from the philosophy of teaching, which distinguishes between training and education:

Training teaches how to carry out a specific task more efficiently and reliably. Education, on the other hand, opens and enriches a person's mind. To train a person, you need know nothing about who they really are, or what they love, or why. Education reaches out to embrace the whole person. Historically, we have treated money as a matter of training, rather than education in its wider and more dignified sense.

Training teaches how to carry out a specific task more efficiently and reliably. Education, on the other hand, opens and enriches a person's mind. To train a person, you need know nothing about who they really are, or what they love, or why. Education reaches out to embrace the whole person. Historically, we have treated money as a matter of training, rather than education in its wider and more dignified sense.

Underpinning our money worries, Armstrong argues, are four main questions that have far less to do with our financial standing than with psychoemotional and social factors – questions about why money is important to us, how much money we need to achieve what's important to us, what the best way to acquire that money is, and what our economic responsibilities to others are in the course of acquiring and using that money. We'll never overcome our money worries, he argues, unless we first recognize those underlying questions:

Our worries – when it comes to money – are about psychology as much as economics, the soul as much as the bank balance.

Our worries – when it comes to money – are about psychology as much as economics, the soul as much as the bank balance.

Key among Armstrong's strategies for alleviating such worries is developing a good relationship with money, which parallels human-to-human dynamics:

One thing that's characteristic of a good relationship is this: you get more accurate at assigning responsibility. When things go wrong you can see how much is your fault and how much is the fault of the other person. And the same holds when things go well. You know that part of it is your doing and part depends on the contribution of your partner.

This model applies to money. When things go well or badly, it's partly about what you bring to the situation and partly about what money brings. What money brings is a certain level of spending power.

What you bring to this relationship includes imagination, values, emotions, attitudes, ambitious, fears, and memories. So the relationship is absolutely not just a matter of pure economic facts of how much you get and how much you spend.

One thing that's characteristic of a good relationship is this: you get more accurate at assigning responsibility. When things go wrong you can see how much is your fault and how much is the fault of the other person. And the same holds when things go well. You know that part of it is your doing and part depends on the contribution of your partner.

This model applies to money. When things go well or badly, it's partly about what you bring to the situation and partly about what money brings. What money brings is a certain level of spending power.

What you bring to this relationship includes imagination, values, emotions, attitudes, ambitious, fears, and memories. So the relationship is absolutely not just a matter of pure economic facts of how much you get and how much you spend.

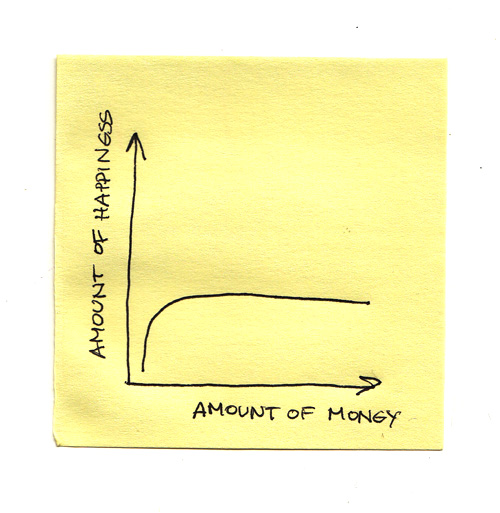

In discussing research indicating that more money, after a certain threshold, doesn't mean more happiness, Armstrong offers a necessary definition of happiness:

When we talk about happiness, what do we have in mind? Probably a mixture of buoyancy and serenity; you feel elated but safe.

When we talk about happiness, what do we have in mind? Probably a mixture of buoyancy and serenity; you feel elated but safe.

The relationship money has to these attributes, he argues, is "real but diminishing." While money can buy the accoutrements of buoyancy – chocolate, weekend getaways, expensive shoes – many people feel unhappy despite having these. His explanation, echoing the philosophy of Alan Watts, leads to the obvious conclusion:

Money can purchase the symbols but not the causes of serenity and buoyancy. In a straightforward way we must agree that money cannot buy happiness.

Money can purchase the symbols but not the causes of serenity and buoyancy. In a straightforward way we must agree that money cannot buy happiness.

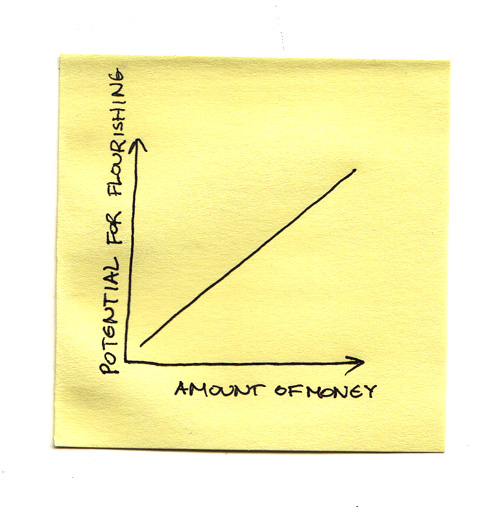

Since Armstrong's main argument is premised on the idea that our culture is geared toward addressing troubles rather than amplifying well-being, which parallels the disconnect that Martin Seligman observed in the field of psychology when he founded the positive psychology movement, it comes as no surprise that Armstrong's key construct in solving the conundrum mirrors Seligman's philosophy of flourishing over "happiness." Indeed, Armstrong argues that while serenity and buoyancy are appealing, they fall short of reflecting what people really want out of life:

Most people realize that they really need to do things for other people. There is a deep fear that one's life will be lived in vain – without making a contribution, or a benign difference, to the lives of others. … Flourishing means getting on with the things that are important for you to do, exercising your capacities, actively trying to "realize" what you care about and bring it into life. But these activities involve anxiety, fear of failure and setbacks, as well as a sense of satisfaction, occasional triumphs and moments of excitement.

Most people realize that they really need to do things for other people. There is a deep fear that one's life will be lived in vain – without making a contribution, or a benign difference, to the lives of others. … Flourishing means getting on with the things that are important for you to do, exercising your capacities, actively trying to "realize" what you care about and bring it into life. But these activities involve anxiety, fear of failure and setbacks, as well as a sense of satisfaction, occasional triumphs and moments of excitement.

And yet this is in no way a motion to flatten the full dimensionality of the human experience:

A good life is still a life. It must involve a full share of suffering, loneliness, disappointment and coming to terms with one's own mortality and the deaths of those one loves. To live a life that is good as a life involves all this.

A good life is still a life. It must involve a full share of suffering, loneliness, disappointment and coming to terms with one's own mortality and the deaths of those one loves. To live a life that is good as a life involves all this.

While the things money can secure – like power, influence, and access to resources – may not be shortcuts to serenity and buoyancy, Armstrong argues, they are inextricably linked to flourishing by enabling you to pursue the things that are important to you and, in the process, to contribute to the lives of others. Here, the relationship between amount of money and potential for flourishing doesn't flatline the way it does in a more narrow conception of happiness:

Armstrong's key point, however, is that while this correlation of growth might be directly proportional, money isn't a cause of flourishing but an ingredient in it, a mere resource with which to build the life we want, catalyzed by virtue:

Money brings about good consequences – helps us live valuable lives – only when joined with "virtues." Virtues are good abilities of mind and character.

Money brings about good consequences – helps us live valuable lives – only when joined with "virtues." Virtues are good abilities of mind and character.

Reminiscent of Ben-Franklian virtues like temperance, frugality, and moderation is another essential skill in alleviating our money worries – the ability to distinguish between wants and needs. The need-desire distinction, Armstrong suggests, is useful in warding off mere desires, like the longing for the latest shiny gadget, even if it's of little utilitarian value, or that sleek new bike, even if the old one works perfectly fine.

If we want to be wise about money we should resist the impulse to follow our desires and concentrate instead on getting what we need.

If we want to be wise about money we should resist the impulse to follow our desires and concentrate instead on getting what we need.

Need is deeper – bound up with the serious narrative of one's life. "Do I need this"? is a way of asking: how important is this thing, how central is it to my becoming a good version of myself; what is it actually for in my life? This interrogation is designed to distinguish needs from mere wants. And that's a good distinction to make.

But it is important to see that this is not the same as the "modest versus grand" distinction. Our needs are not always for the smaller, lesser, cheaper thing.

The ultimate purpose of purchases, he argues, is to help us flourish. His strategy for mastering the needs/wants balance thus rests on not conflating this dichotomy with familiar ones like basic/refined ("a distinction about the level of complexity of an object") or cheap/luxurious ("a distinction to do with price and demand"). Instead, he recommends a seemingly counter-intuitive approach – to consider our…

:: READ FULL ARTICLE / SHARE ::

"When you step away from the prepackaged structure of traditional education, you’ll discover that there are many more ways to learn outside school than within."

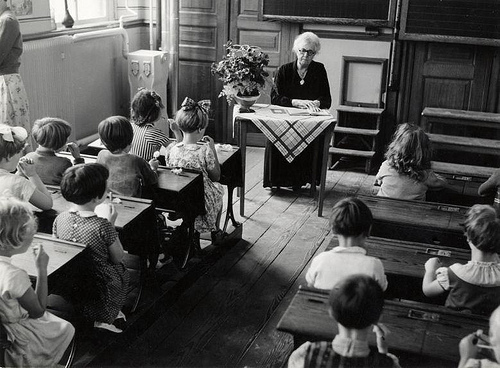

"The present education system is the trampling of the herd," legendary architect Frank Lloyd Wright lamented in 1956. Half a century later, I started Brain Pickings in large part out of frustration and disappointment with my trampling experience of our culturally fetishized "Ivy League education." I found myself intellectually and creatively unstimulated by the industrialized model of the large lecture hall, the PowerPoint presentations, the standardized tests assessing my rote memorization of facts rather than my ability to transmute that factual knowledge into a pattern-recognition mechanism that connects different disciplines to cultivate wisdom about how the world works and a moral lens on how it should work. So Brain Pickings became the record of my alternative learning, of that cross-disciplinary curiosity that took me from art to psychology to history to science, by way of the myriad pieces of knowledge I discovered – and connected – on my own. I didn't live up to the entrepreneurial ideal of the college drop-out and begrudgingly graduated "with honors," but refused to go to my own graduation and decided never to go back to school. Years later, I've learned more in the course of writing and researching the thousands of articles to date than in all the years of my formal education combined.

"The present education system is the trampling of the herd," legendary architect Frank Lloyd Wright lamented in 1956. Half a century later, I started Brain Pickings in large part out of frustration and disappointment with my trampling experience of our culturally fetishized "Ivy League education." I found myself intellectually and creatively unstimulated by the industrialized model of the large lecture hall, the PowerPoint presentations, the standardized tests assessing my rote memorization of facts rather than my ability to transmute that factual knowledge into a pattern-recognition mechanism that connects different disciplines to cultivate wisdom about how the world works and a moral lens on how it should work. So Brain Pickings became the record of my alternative learning, of that cross-disciplinary curiosity that took me from art to psychology to history to science, by way of the myriad pieces of knowledge I discovered – and connected – on my own. I didn't live up to the entrepreneurial ideal of the college drop-out and begrudgingly graduated "with honors," but refused to go to my own graduation and decided never to go back to school. Years later, I've learned more in the course of writing and researching the thousands of articles to date than in all the years of my formal education combined.

So, in 2012, when I found out that writer Kio Stark was crowdfunding a book that would serve as a manifesto for learning outside formal education, I eagerly chipped in. Now, Don't Go Back to School: A Handbook for Learning Anything is out and is everything I could've wished for when I was in college, an essential piece of cultural literacy, at once tantalizing and practically grounded assurance that success doesn't lie at the end of a single highway but is sprinkled along a thousand alternative paths. Stark describes it as "a radical project, the opposite of reform … not about fixing school [but] about transforming learning – and making traditional school one among many options rather than the only option." Through a series of interviews with independent learners who have reached success and happiness in fields as diverse as journalism, illustration, and molecular biology, Stark – who herself dropped out of a graduate program at Yale, despite being offered a prestigious fellowship – cracks open the secret to defining your own success and finding your purpose outside the factory model of formal education. She notes the patterns that emerge:

People who forgo school build their own infrastructures. They create and borrow and reinvent the best that formal schooling has to offer, and they leave the worst behind. That buys them the freedom to learn on their own terms. … From their stories, you’ll see that when you step away from the prepackaged structure of traditional education, you’ll discover that there are many more ways to learn outside school than within.

People who forgo school build their own infrastructures. They create and borrow and reinvent the best that formal schooling has to offer, and they leave the worst behind. That buys them the freedom to learn on their own terms. … From their stories, you’ll see that when you step away from the prepackaged structure of traditional education, you’ll discover that there are many more ways to learn outside school than within.

Reflecting on her own exit from academia, Stark articulates a much more broadly applicable insight:

A gracefully executed quit is a beautiful thing, opening up more doors than it closes.

A gracefully executed quit is a beautiful thing, opening up more doors than it closes.

But despite discovering in dismay that "liberal arts graduate school is professional school for professors," which she had no interest in becoming, Stark did learn something immensely valuable from her third year of independent study, during which she read about 200 books of her own choosing:

I learned how to teach myself. I had to make my own reading lists for the exams, which meant I learned how to take a subject I was interested in and make myself a map for learning it.

I learned how to teach myself. I had to make my own reading lists for the exams, which meant I learned how to take a subject I was interested in and make myself a map for learning it.

The interviews revealed four key common tangents: learning is collaborative rather than done alone; the importance of academic credentials in many professions is declining; the most fulfilling learning tends to take place outside of school; and those happiest about learning are those who learn out of intrinsic motivation rather than in pursuit of extrinsic rewards. The first of these insights, of course, appears on the surface to contradict the very notion of "independent learning," but Stark offers an eloquent semantic caveat:

Independent learning suggests ideas such as “self-taught,” or “autodidact.” These imply that independence means working solo. But that’s just not how it happens. People don’t learn in isolation. When I talk about independent learners, I don’t mean people learning alone. I’m talking about learning that happens independent of schools. … Anyone who really wants to learn without school has to find other people to learn with and from. That’s the open secret of learning outside of school. It’s a social act. Learning is something we do together.

Independent learning suggests ideas such as “self-taught,” or “autodidact.” These imply that independence means working solo. But that’s just not how it happens. People don’t learn in isolation. When I talk about independent learners, I don’t mean people learning alone. I’m talking about learning that happens independent of schools. … Anyone who really wants to learn without school has to find other people to learn with and from. That’s the open secret of learning outside of school. It’s a social act. Learning is something we do together.

Independent learners are interdependent learners.

She critiques the present boom of massive open online classes, or MOOCs, for their tendency to attempt replicating the offline experience online rather than building a new model for learning from the ground up:

Simply put, MOOCs are designed to put teaching online, and that is their mistake. Instead they should start putting learning online. The innovation of MOOCs is to detach the act of teaching from physical classrooms and tuition-based enrollment. But what they should be working toward is much more radical – detaching learning from the linear processes of school.

Simply put, MOOCs are designed to put teaching online, and that is their mistake. Instead they should start putting learning online. The innovation of MOOCs is to detach the act of teaching from physical classrooms and tuition-based enrollment. But what they should be working toward is much more radical – detaching learning from the linear processes of school.

But that, Stark found, is missing the point. When she interviewed people who did go to school and asked what they most liked about the experience, they "unanimously cited 'other people' as the most useful and meaningful part of their school experience." So, then:

Given the primacy of community in the experience of learning, the question of how to take the auto out of autodidactic is the first and most central question for learners.

Given the primacy of community in the experience of learning, the question of how to take the auto out of autodidactic is the first and most central question for learners.

Much of the argument for formal education rests on statistics indicating that people with college and graduate degrees earn more. But those statistics, Stark notes, suffer an important and rarely heeded bias:

The problem is that this statistic is based on long-term data, gathered from a period of moderate loan debt, easy employability, and annual increases in the value of a college degree. These conditions have been the case for college grads for decades. Given the dramatically changed circumstances grads today face, we already know that the trends for debt, employability, and the value of a degree have all degraded, and we cannot assume the trend toward greater lifetime earnings will hold true for the current generation. This is a critical omission from media coverage. The fact is we do not know. There’s absolutely no guarantee it will hold true.

The problem is that this statistic is based on long-term data, gathered from a period of moderate loan debt, easy employability, and annual increases in the value of a college degree. These conditions have been the case for college grads for decades. Given the dramatically changed circumstances grads today face, we already know that the trends for debt, employability, and the value of a degree have all degraded, and we cannot assume the trend toward greater lifetime earnings will hold true for the current generation. This is a critical omission from media coverage. The fact is we do not know. There’s absolutely no guarantee it will hold true.

Some heartening evidence suggests the blind reliance on degrees might be beginning to change. Stark cites Zappos CEO Tony Hsieh:

I haven’t looked at a résumé in years. I hire people based on their skills and whether or not they are going to fit our culture.

I haven’t looked at a résumé in years. I hire people based on their skills and whether or not they are going to fit our culture.

Another common argument for formal education extols the alleged advantages of its structure, proposing that homework assignments, reading schedules, and regular standardized testing would motivate you to learn with greater rigor. But, as Daniel Pink has written about the psychology of motivation, in school, as in work, intrinsic drives far outweigh extrinsic, carrots-and-sticks paradigms of reward and punishment, rendering this argument unsound. Stark writes:

Learning outside school is necessarily driven by an internal engine. … [I]ndependent learners stick with the reading, thinking, making, and experimenting by which they learn because they do it for love, to scratch an itch, to satisfy curiosity, following the compass of passion and wonder about the world.

Learning outside school is necessarily driven by an internal engine. … [I]ndependent learners stick with the reading, thinking, making, and experimenting by which they learn because they do it for love, to scratch an itch, to satisfy curiosity, following the compass of passion and wonder about the world.

So how can you best fuel that internal engine of learning outside the depot of formal education? Stark offers an essential insight, which places self-discovery at the heart of acquiring external knowledge:

Learning your own way means finding the methods that work best for you and creating conditions that support sustained motivation. Perseverance, pleasure, and the ability to retain what you learn are among the wonderful byproducts of getting to learn using methods that suit you best and in contexts that keep you going. Figuring out your personal approach to each of these takes trial and error. … For independent learners, it’s essential to find the process and methods that match your instinctual tendencies as a learner. Everyone I talked to went through a period of experimenting and sorting out what works for them, and they’ve become highly aware of their own preferences. They’re clear that learning by methods that don’t suit them shuts down their drive and diminishes their enjoyment of learning. Independent learners also find that their preferred methods are different for different areas. So one of the keys to success and enjoyment as an independent learner is to discover how you learn. … School isn’t very good at dealing with the multiplicity of individual learning preferences, and it’s not very good at helping you figure out what works for you.

Learning your own way means finding the methods that work best for you and creating conditions that support sustained motivation. Perseverance, pleasure, and the ability to retain what you learn are among the wonderful byproducts of getting to learn using methods that suit you best and in contexts that keep you going. Figuring out your personal approach to each of these takes trial and error. … For independent learners, it’s essential to find the process and methods that match your instinctual tendencies as a learner. Everyone I talked to went through a period of experimenting and sorting out what works for them, and they’ve become highly aware of their own preferences. They’re clear that learning by methods that don’t suit them shuts down their drive and diminishes their enjoyment of learning. Independent learners also find that their preferred methods are different for different areas. So one of the keys to success and enjoyment as an independent learner is to discover how you learn. … School isn’t very good at dealing with the multiplicity of individual learning preferences, and it’s not very good at helping you figure out what works for you.

Echoing Neil deGrasse Tyson, who has argued that "every child is a scientist" since curiosity is coded into our DNA, and Sir Ken Robinson, who has lamented that the industrial model of education schools us out of our inborn curiosity, Stark observes:

Any young child you observe displays these traits. But passion and curiosity can be easily lost. School itself can be a primary cause; arbitrary motivators such as grades leave little room for variation in students’ abilities and interests, and fail to reward curiosity itself. There are also significant social factors working against children’s natural curiosity and capacity for learning, such as…

Any young child you observe displays these traits. But passion and curiosity can be easily lost. School itself can be a primary cause; arbitrary motivators such as grades leave little room for variation in students’ abilities and interests, and fail to reward curiosity itself. There are also significant social factors working against children’s natural curiosity and capacity for learning, such as…

:: READ FULL ARTICLE / SHARE ::

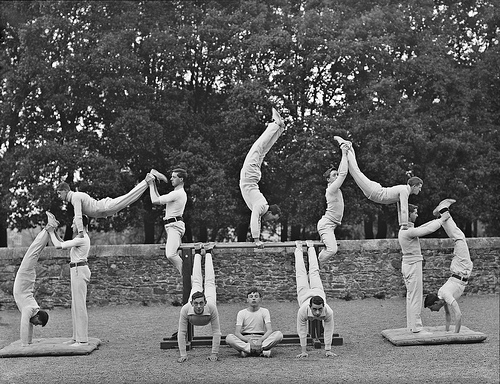

"Make New Mistakes. Make glorious, amazing mistakes. Make mistakes nobody's ever made before."

Commencement season is upon us and, after Greil Marcus's soul-stirring speech on the essence of art at the 2013 School of Visual Arts graduation ceremony, here comes an exceptional adaptation of one of the best commencement addresses ever delivered: In May of 2012, beloved author Neil Gaiman stood up in front of the graduating class at Philadelphia's University of the Arts and dispensed some timeless advice on the creative life; now, his talk comes to life as a slim but potent book titled Make Good Art (public library).

Commencement season is upon us and, after Greil Marcus's soul-stirring speech on the essence of art at the 2013 School of Visual Arts graduation ceremony, here comes an exceptional adaptation of one of the best commencement addresses ever delivered: In May of 2012, beloved author Neil Gaiman stood up in front of the graduating class at Philadelphia's University of the Arts and dispensed some timeless advice on the creative life; now, his talk comes to life as a slim but potent book titled Make Good Art (public library).

Best of all, it's designed by none other than the inimitable Chip Kidd, who has spent the past fifteen years shaping the voice of contemporary cover design with his prolific and consistently stellar output, ranging from bestsellers like cartoonist Chris Ware's sublime Building Stories and neurologist Oliver Sacks's The Mind's Eye to lesser-known gems like The Paris Review's Women Writers at Work and The Letter Q, that wonderful anthology of queer writers' letters to their younger selves. (Fittingly, Kidd also designed the book adaptation of Ann Patchett's 2006 commencement address.)

When things get tough, this is what you should do: Make good art. I’m serious. Husband runs off with a politician – make good art. Leg crushed and then eaten by a mutated boa constrictor – make good art. IRS on your trail – make good art. Cat exploded – make good art. Someone on the Internet thinks what you’re doing is stupid or evil or it’s all been done before – make good art. Probably things will work out somehow, eventually time will take the sting away, and that doesn’t even matter. Do what only you can do best: Make good art. Make it on the bad days, make it on the good days, too.

When things get tough, this is what you should do: Make good art. I’m serious. Husband runs off with a politician – make good art. Leg crushed and then eaten by a mutated boa constrictor – make good art. IRS on your trail – make good art. Cat exploded – make good art. Someone on the Internet thinks what you’re doing is stupid or evil or it’s all been done before – make good art. Probably things will work out somehow, eventually time will take the sting away, and that doesn’t even matter. Do what only you can do best: Make good art. Make it on the bad days, make it on the good days, too.

A wise woman once said, "If you are not making mistakes, you're not taking enough risks." Gaiman articulates the same sentiment with his own brand of exquisite eloquence:

I hope that in this year to come, you make mistakes.

I hope that in this year to come, you make mistakes.

Because if you are making mistakes, then you are making new things, trying new things, learning, living, pushing yourself, changing yourself, changing your world. You're doing things you've never done before, and more importantly, you're Doing Something.

So that's my wish for you, and all of us, and my wish for myself. Make New Mistakes. Make glorious, amazing mistakes. Make mistakes nobody's ever made before. Don't freeze, don't stop, don't worry that it isn't good enough, or it isn't perfect, whatever it is: art, or love, or work or family or life.

Whatever it is you're scared of doing, Do it.

Make your mistakes, next year and forever.

Revisit the talk in its original delivery below, and reabsorb its eight indispensable lessons:

:: READ FULL ARTICLE / WATCH / SHARE ::